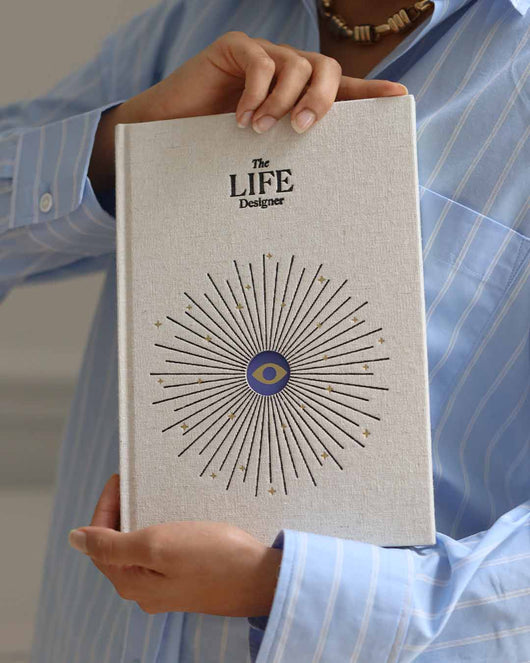

Featured On

幸运飞行艇全新开奖结果号码,168飞艇现场开奖直播网址,幸运168飞艇开奖号码历史记录 Shop by Category

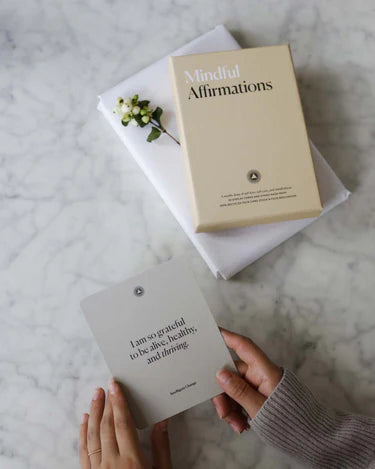

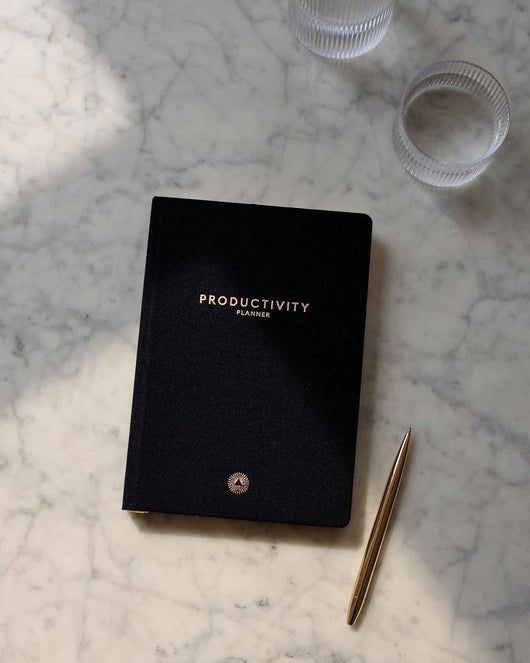

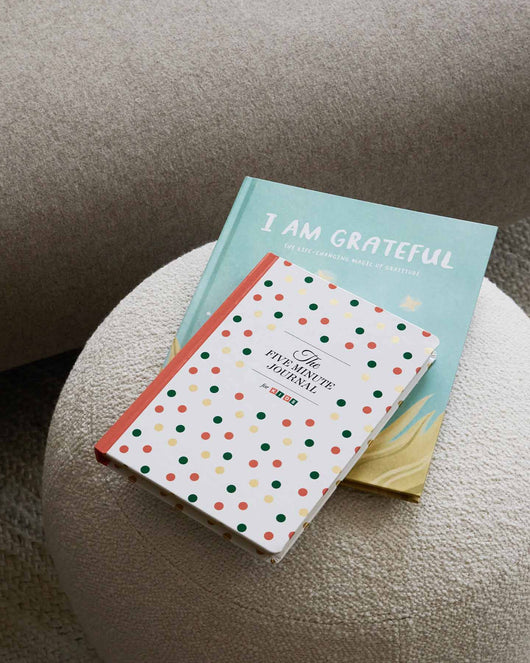

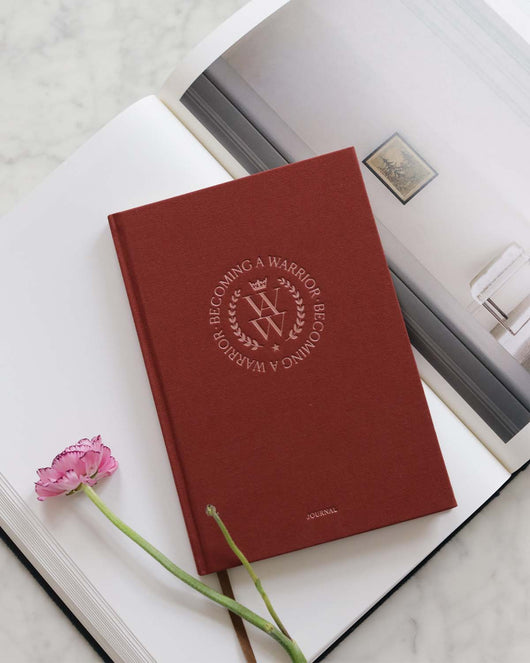

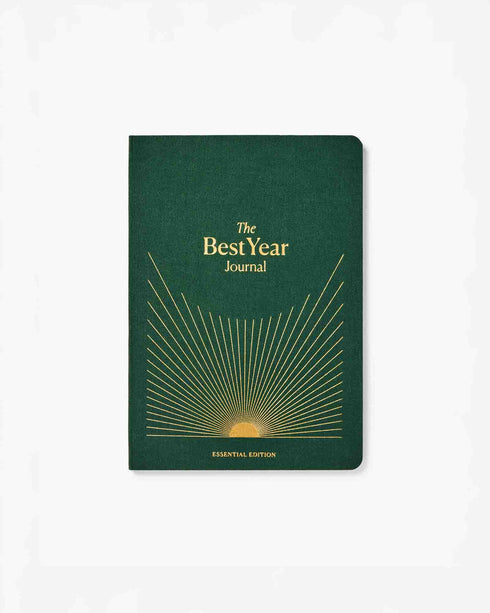

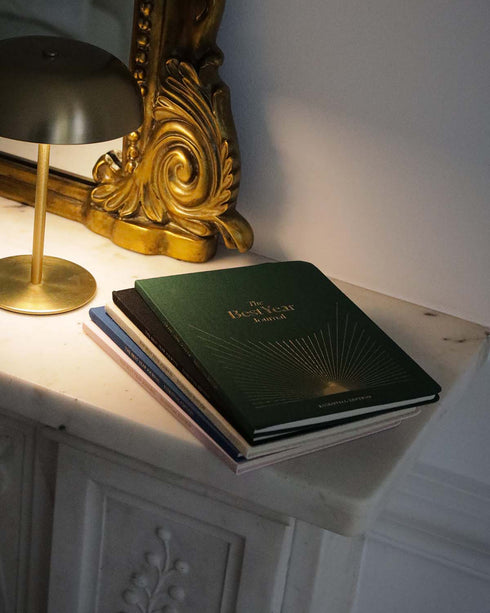

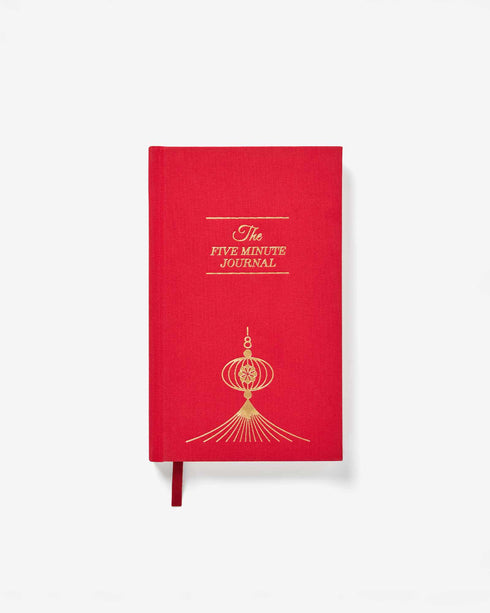

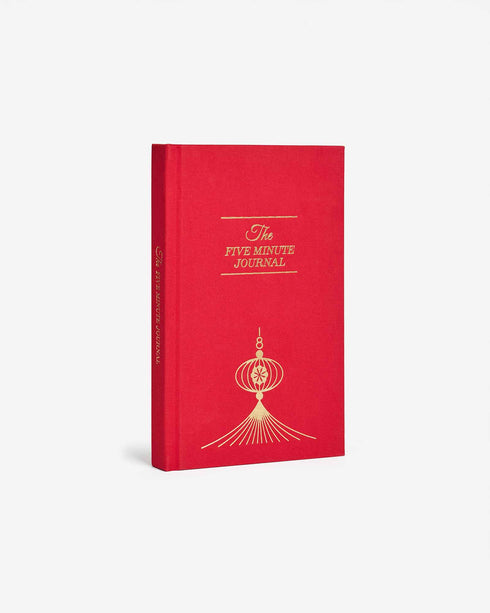

OUR PHILOSOPHY

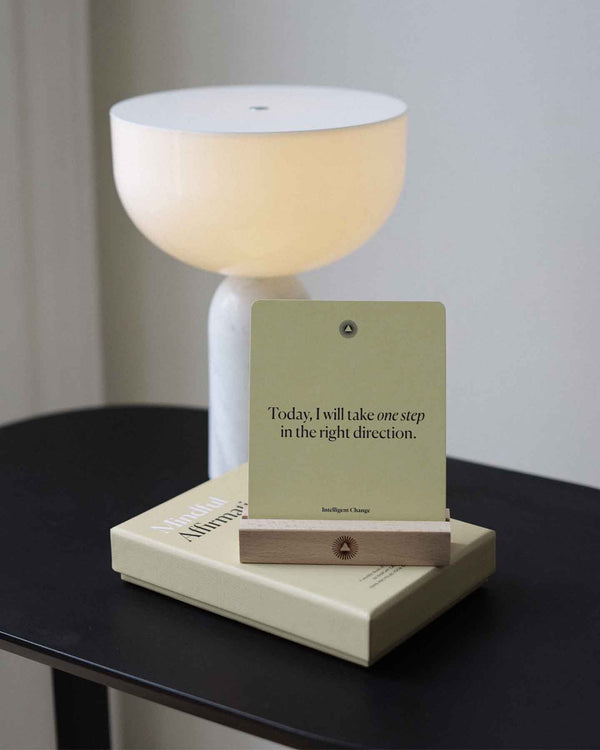

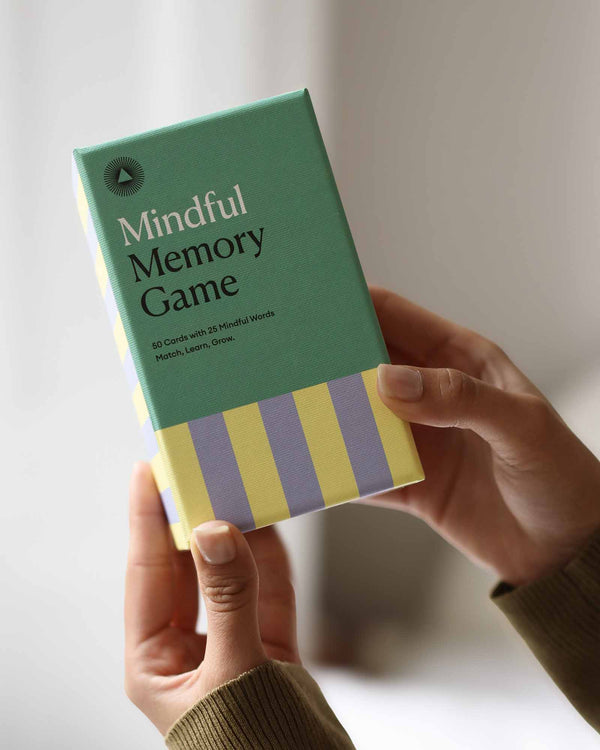

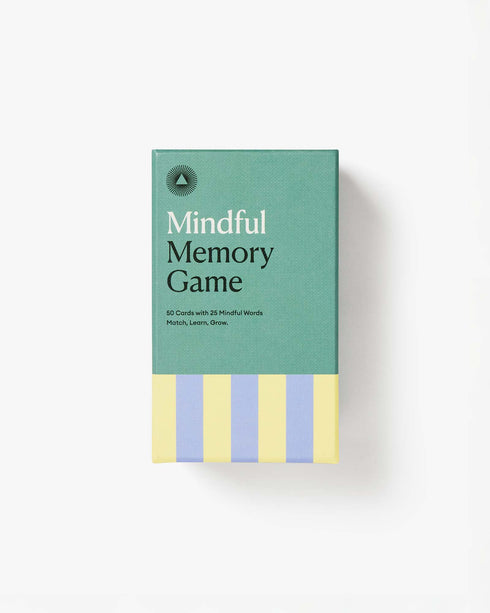

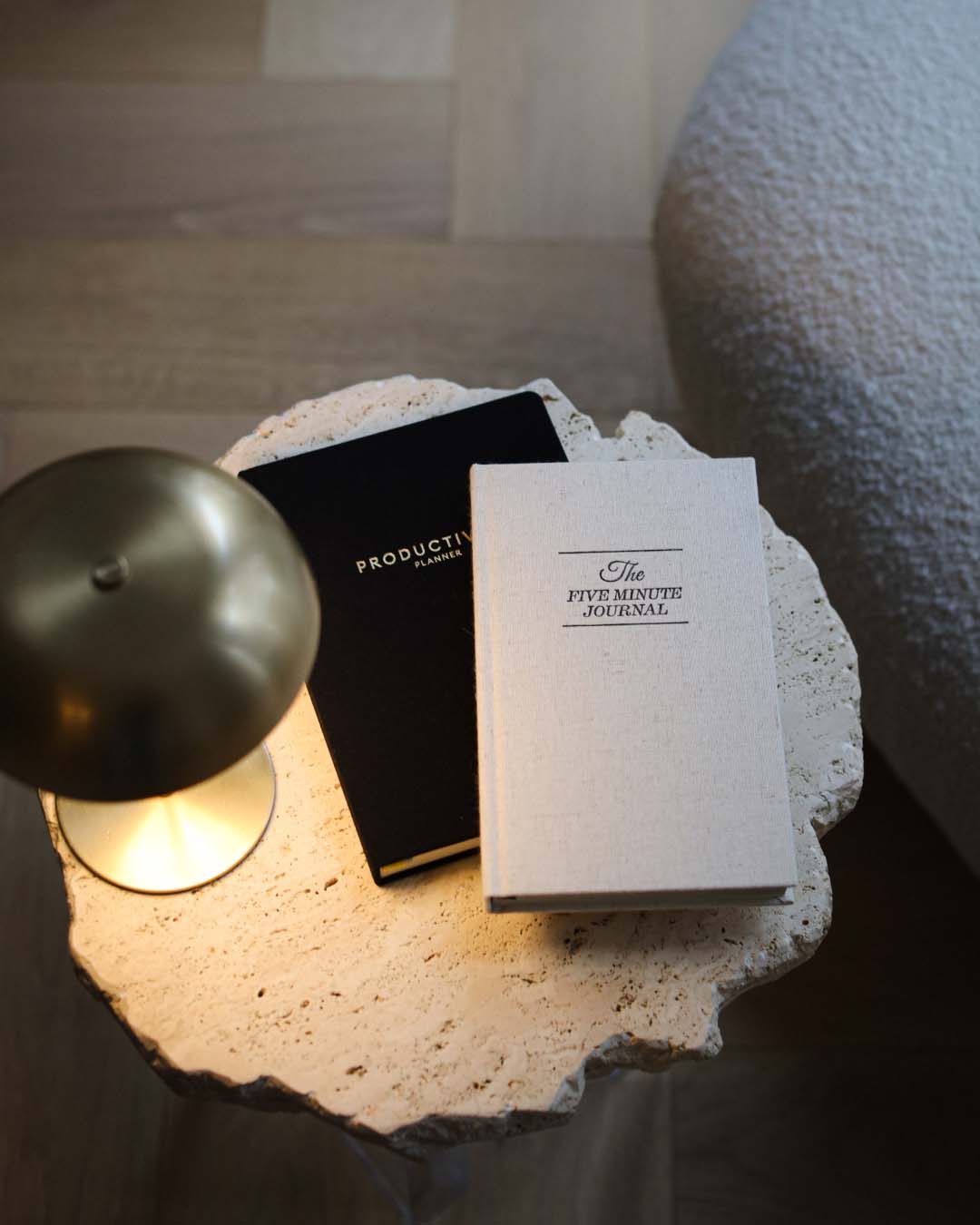

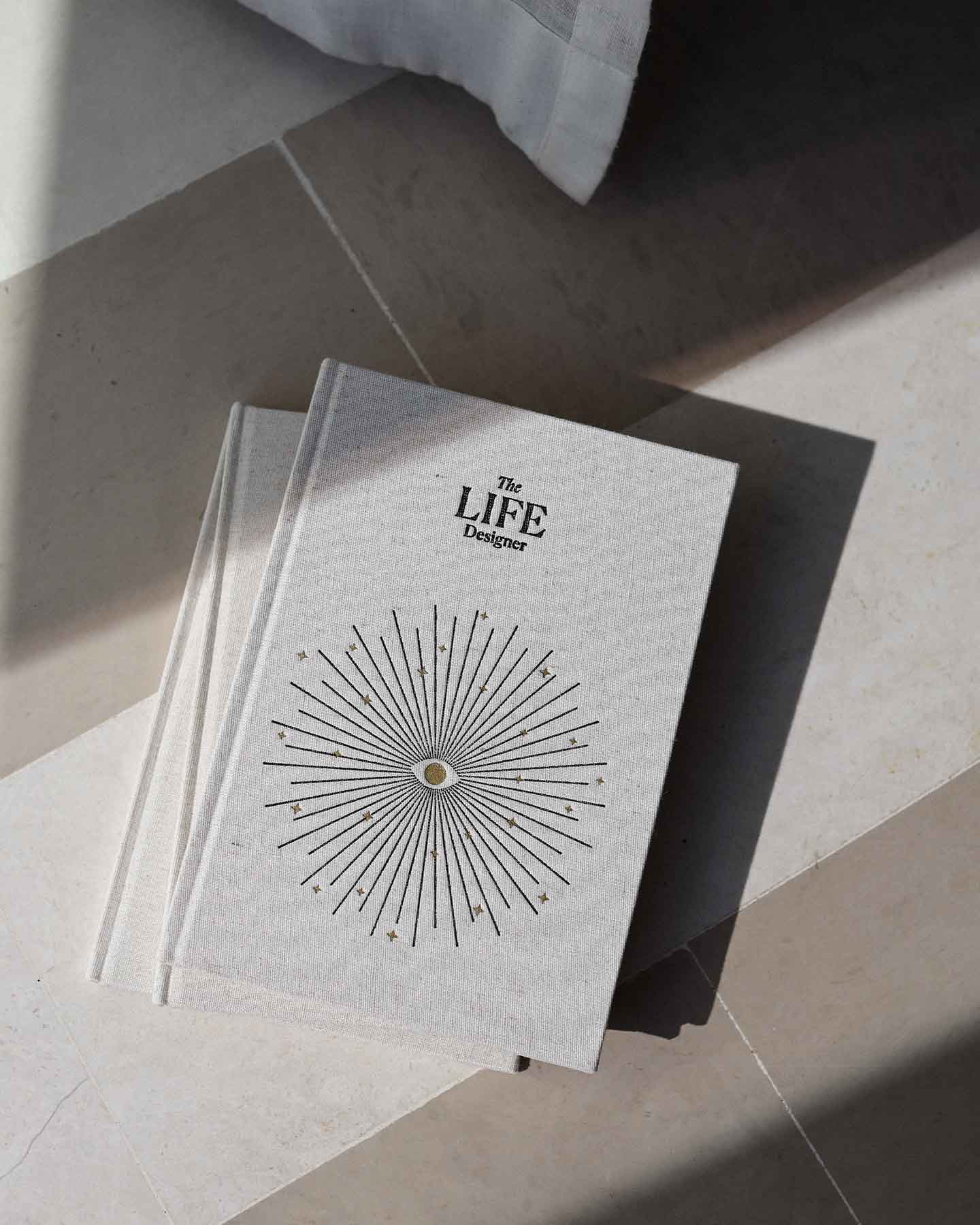

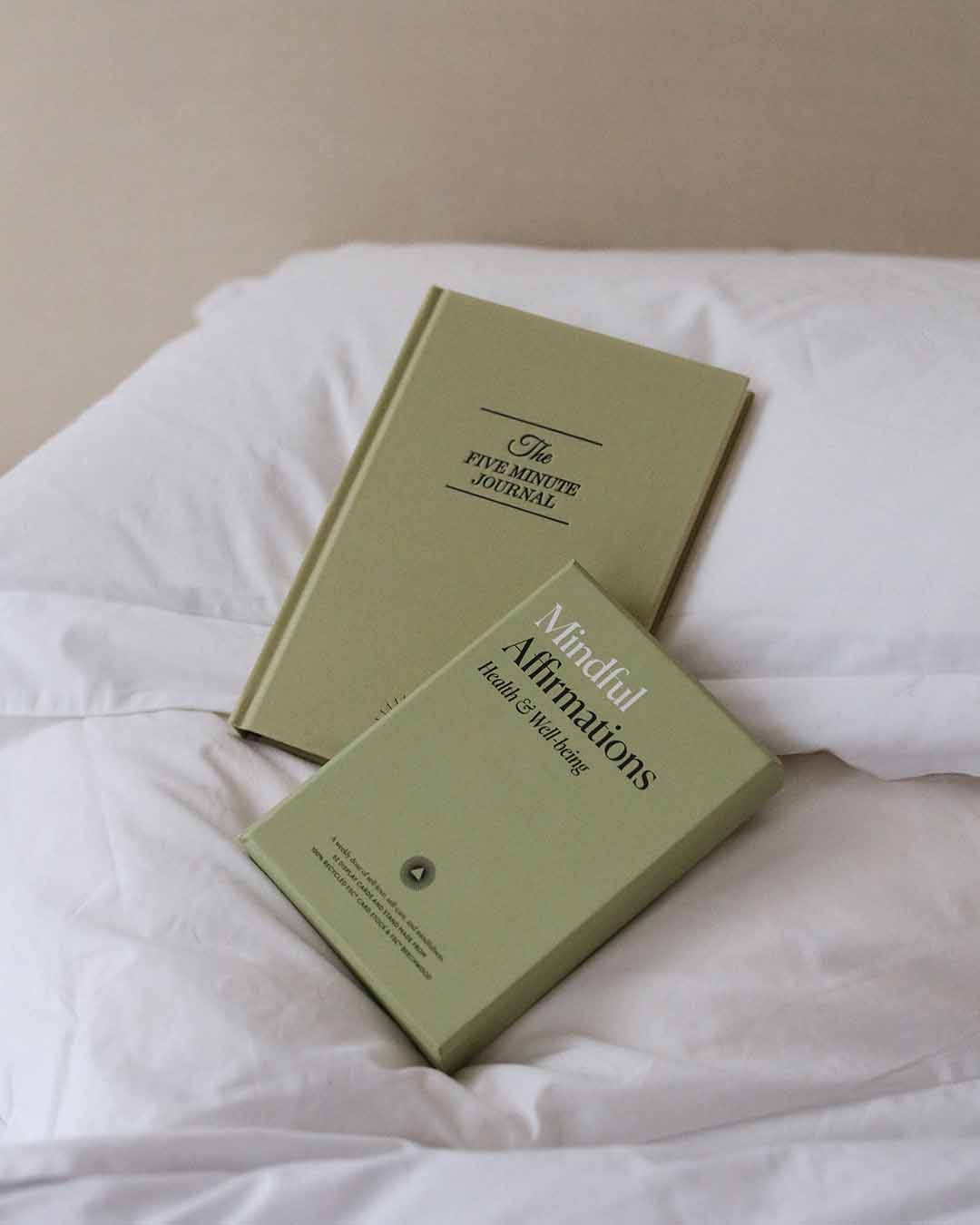

We create elevated, thoughtfully designed products to help you realize your potential and live a happier, more fulfilling life.

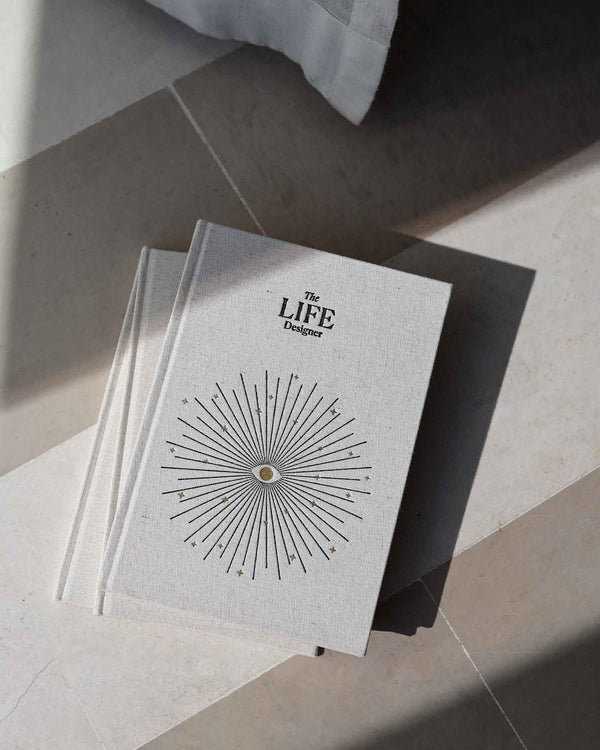

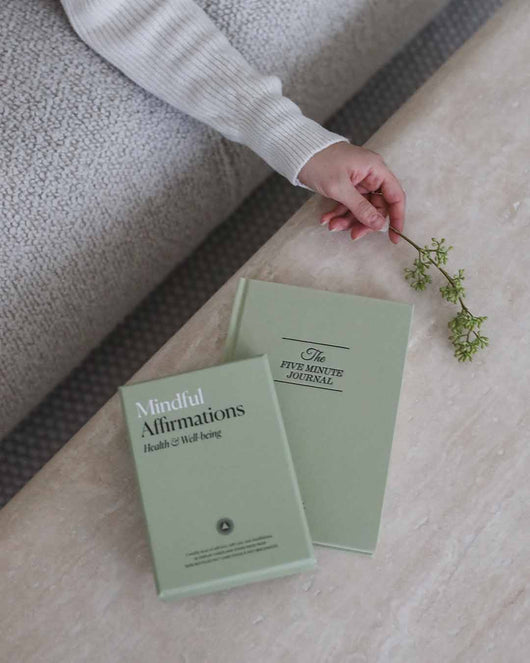

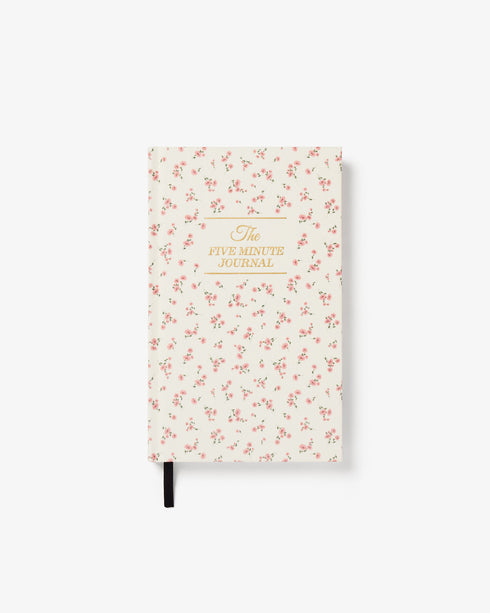

幸运168飞行艇全天精准计划,飞艇168全国开奖官网直播,幸运飞行艇最新开奖结果查询+官方开奖历史记录. Premium doesn't mean wasteful. We use natural, recycled, and compostable materials to protect our shared home.

100% compostable

100% PLASTIC FREE

100% RECYCLED FSC™ PAPER

100% NATURAL MATERIALS

Choose Intelligent Change

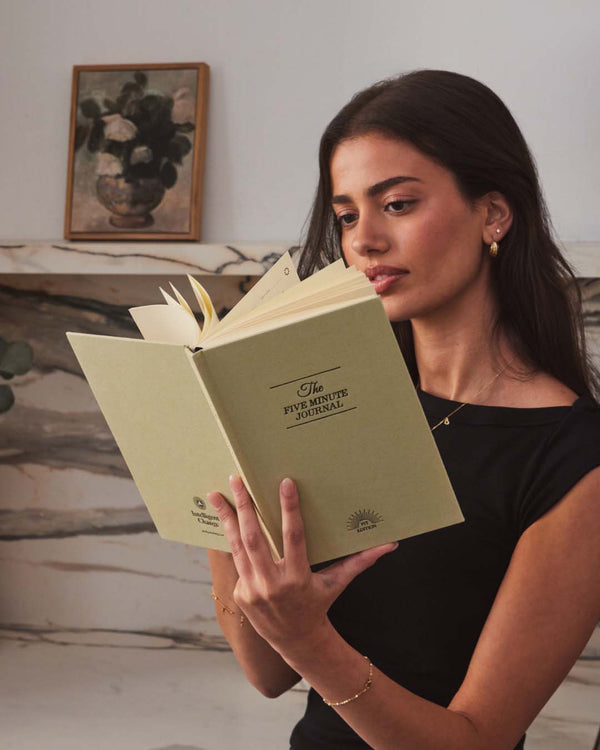

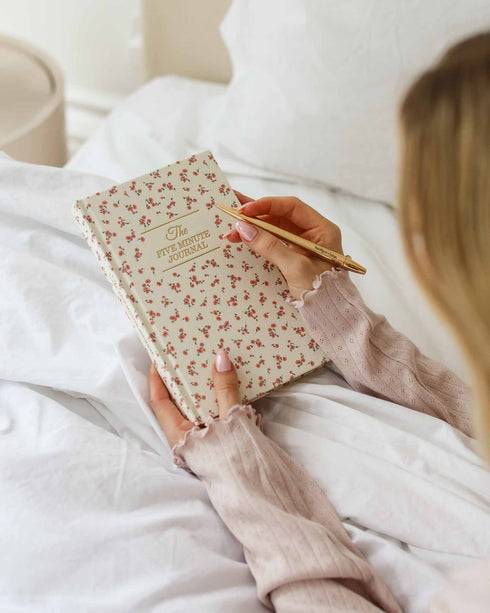

Research-Driven, User-Approved

We’ve helped over two million people around the world, just like you, improve their lives.

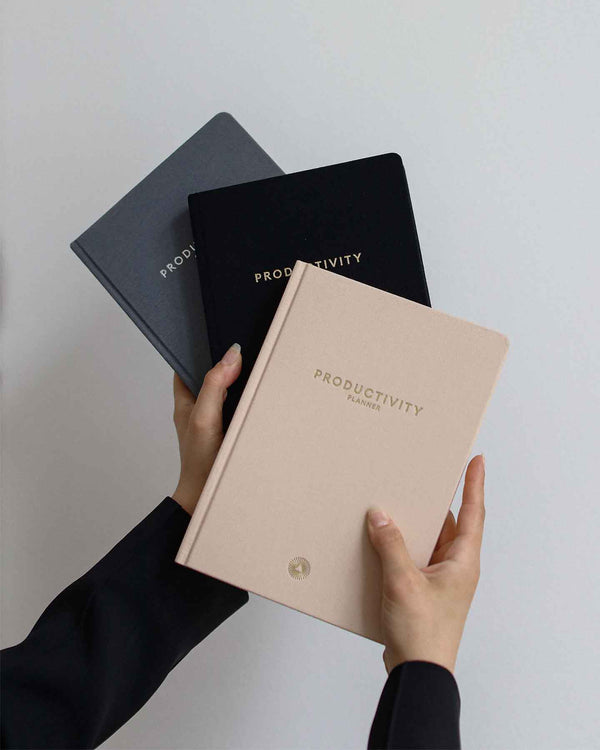

Positive Transformation, Risk-Free

We offer a 6 month money-back guarantee because we're confident you’ll experience transformative change.

Personal growth with the planet in mind

We use natural, recycled, and compostable materials and are plastic-free.

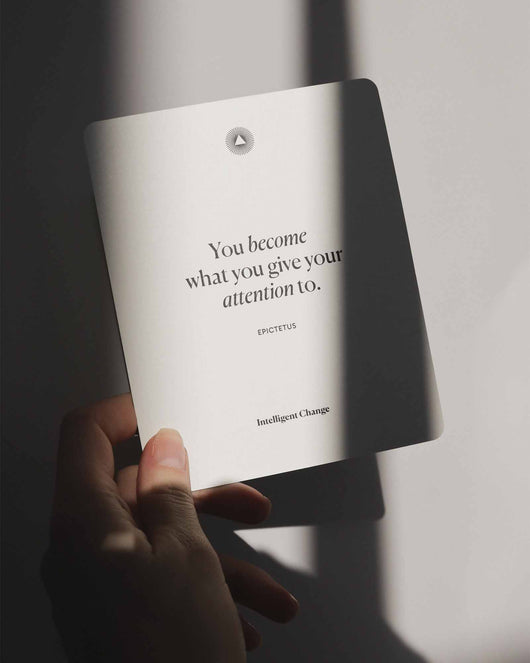

"全场飞艇2025官网历史记录,直播飞行艇168开奖官网,幸运飞行艇号码查询 Always remember, your focus determines your reality."

George Lucas

Free Shipping

Enjoy FREE Shipping on U.S. orders over $75*. Intelligent Change also ships worldwide.

100% Secure Checkout

Shop with confidence that your purchase is safe and secure throughout the checkout process.

6 Month Money-Back Guarantee

Because we’re confident you’ll experience transformative change.